The study aims to highlight the prehistory, the processes of formation, development and dialect division of the Old Russian people. Until now, archaeological materials have not been involved in a holistic solution of this problem. Linguists repeatedly turned to the questions of the history and dialectology of the Old Russian language, as a result of which the linguistic questions themselves turned out to be more developed than the historical ones. On the part of historians, attempts to illuminate the essence of the Old Russian people were less productive, since historical science does not have a sufficient source base in solving ethnogenetic topics. The use of archeological data in the study of the origins and evolution of the Old Russian ethnos, taking into account all the results obtained so far by other sciences, seems to be very promising. This is the purpose of the proposed work.

The archaeological materials collected by many generations of researchers have now made up a huge source fund, which is increasingly being used to study the complex historical processes that took place in Eastern Europe in antiquity and the Middle Ages. Based on archeological data, important results have already been obtained on a number of historical and ethnocultural topics that could not be resolved on the basis of information from historical sources that has come down to us. It seems that the time has come for the widest use of materials from archeology and in research on the complex problem of the formation of the Old Russian people, revealing its content and conditions for differentiation.

The book opens with a historiographical section that outlines the process of developing knowledge about this medieval ethnos. The research part consists of several sections. In order to understand the historical period preceding the formation of the ancient Russian nationality, it was necessary to shed light on its prehistory in the most detailed way. It turns out that the process of mastering the East European Plain by the Slavs was very complex and multi-act. Colonization was carried out from different sides and by various ethnographic Proto-Slavic groups. The heterogeneity of the Slavic population of Eastern Europe was aggravated by the fact that in different places the Slavs found multi-ethnic natives (various Finnish-speaking tribes in the forest belt, a heterogeneous Baltic population in the Upper Dnieper and adjacent lands, Iranian-speaking and Turkic tribes in the South). On the eve of the formation of the Old Russian people on the East European Plain, several large ethno-tribal groups are archaeologically recorded Slavic ethnic group, some of which were represented by dialect formations of the Late Proto-Slavic period. These groups in some cases are not comparable with chronicle tribes.

Based on archaeological materials, powerful integration phenomena that took place on the East European Plain in the last centuries of the 1st millennium AD are revealed. e., which consolidated the heterogeneous Slavs, led to its cultural unity, and ultimately to the formation of an ethno-linguistic community - the Old Russian people. An independent section is devoted to the study of these integration phenomena, among which the wide infiltration of the Danube Slavs into Eastern European lands, which was first discovered on the basis of archeological data.

The heterogeneous ethno-tribal composition of the Old Russian people was reflected in its dialect structure, reconstructed on the basis of archaeological materials, and in the fragmentation of its territory into historical lands, which became separate political entities during the period of feudal fragmentation of Russia. However, in this situation, the East Slavic ethno-linguistic community continued its unified development for some time, both culturally and ethnically.

Only the Tatar-Mongol yoke and the inclusion of significant parts of the East Slavic territories into the Lithuanian state broke the unity of the ancient Russian people. A gradual process of formation of the Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian ethnic groups began.

This is the essence of the proposed study.

In an effort to draw a holistic picture of the ethnic history of the Slavic population of Eastern Europe, the author had to develop a number of topics that have not yet received adequate coverage in the scientific literature. Thus, the work establishes that in the northern part of the East Slavic area, the Slavic population appeared not on the eve of the formation of the Old Russian state, as it seemed recently, but even during the Great Migration of Peoples. The problem of the Rus, one of the formations of the Proto-Slavic era, is also illuminated in a new way.

The history of the study of the problem of ancient Russian nationality

This problem attracted the attention of researchers already in the first half of the 19th century. At an early stage, it was considered mainly on the basis of linguistic materials, which is quite understandable, since language is the most important marker of any ethnic formation. Among Russian scientists, A. Kh. Vostokov was the first to try to highlight the topic under consideration. Having identified some of the distinctive features of the Old Russian dialects, the researcher argued that the Old Russian language stood out from the common Slavic. He dated the emergence of differences between the individual Slavic languages of the 12th-13th centuries, believing that at the time of Cyril and Methodius, all Slavs still understood each other relatively easily, that is, they used the common Slavic language.

This issue was studied somewhat more specifically by I. I. Sreznevsky, who believed that the common Slavic (Proto-Slavic) language was initially divided into two branches - western and southeastern, and the latter, after some time, differentiated into Old Russian and South Slavic languages. The researcher attributed the beginning of the Old Russian language to the 9th–10th centuries. During this period it was still monolithic. Dialectal features in the Old Russian language, according to the research of I. I. Sreznevsky, appear in the XI-XIV centuries, and in the XV century. on its basis, the Great Russian (with division into the North Great Russian and South Great Russian groups, the latter with a Belarusian sub-dialect) and Little Russian (Ukrainian) dialects are formed.

P. A. Lavrovsky explained the division of the Old Russian language into the Great Russian and Little Russian dialects by the historical situation - the formation in the time of Andrei Bogolyubsky of a state independent of Kyiv in North-Eastern Russia. This linguist first expressed the idea of the early, even before the appearance of writing in Russia, the formation of the Old Novgorod dialect, which, however, did not meet with support among scientists of the 19th century.

In the second half of the last century, the tradition of deriving the Old Russian language from Proto-Slavic took root in linguistic literature completely. Only a few scholars have sporadically taken a different view. So, the historian M.P. Pogodin expressed the idea that the Kievan land was originally “originally Great Russian”, and Galician Rus was “Little Russian”. The Tatar-Mongol invasion significantly devastated the Kiev region, after which it was occupied by immigrants from Galicia and thus became Little Russian. A different opinion was held by M.A. Maksimovich, who believed that the population of Kievan Rus was Ukrainian. According to this researcher, the Ukrainian ethnos was preserved in the southern lands of Russia in the subsequent time, right up to the present. There was no desolation of the territory of modern Ukraine either in the Tatar-Mongolian period or ever before.

From historical and dialectological studies of the ancient Russian ethno-linguistic community of this period highest value have the work of A. I. Sobolevsky. Based on the analysis of ancient Russian written monuments of the XI-XIV centuries. this researcher singled out and characterized the features of the Novgorod, Pskov, Smolensk-Polotsk, Kiev and Volyn-Galician dialects within the Old Russian language. He believed that the dialect division of the Old Russian language corresponded to the tribal division of the Eastern Slavs of the previous period.

The first serious historical and linguistic understanding of the beginning of the East Slavic ethno-linguistic community, the process of formation, development, dialect structure and decay of the Old Russian language belongs to A. A. Shakhmatov. Throughout his fruitful activity, this scientist somewhat changed and improved his views on this issue. I will confine myself here to a brief presentation of the essence of the constructions to which A. A. Shakhmatov came to in the last periods of his scientific work.

The first stage in the emergence of Russians (as the researcher called the Eastern Slavs), who separated from the southeastern branch of the Proto-Slavism, A. A. Shakhmatov dated the 5th-6th centuries. The "first ancestral home" of the emerging East Slavic ethnos was the lands in the interfluve of the lower reaches of the Prut and Dniester. These were the Antes, mentioned in historical sources of the 6th-7th centuries. and became the core of the Eastern Slavs. In the 6th century, fleeing the Avars, a significant part of the Ants moved to Volhynia and the Middle Dnieper region. A. A. Shakhmatov called this region “the cradle of the Russian tribe”, since the Eastern Slavs here constituted “one ethnographic whole”. In the IX-X centuries. from this area began a wide settlement of the East Slavic ethnic group, which mastered wide areas from the Black Sea to Ilmen and from the Carpathians to the Don.

The period from the 9th–10th to the 13th century, according to A. A. Shakhmatov, was the next stage in the history of the Eastern Slavs, which he calls Old Russian. As a result of settlement, the Eastern Slavs at that time differentiated into three large dialects - North Russian, East Russian (or Central Russian) and South Russian. The North Russians are that part of the Eastern Slavs who advanced to the upper reaches of the Dnieper and Western Dvina, to the basins of the Ilmensky and Peipsi lakes, and also settled the interfluve of the Volga and Oka. As a result, a political union was formed here, in which the Krivichi occupied a dominant position and into which the Finnish-speaking tribes were drawn - Merya, Ves, Chud and Muroma. To the east of the Dnieper and in the Don basin, an East Russian dialect was formed, in which akanye originally developed. The Ukrainian language and its dialects became the linguistic basis for the reconstruction of the South Russian dialect, in connection with which the South Russians A.A. The researcher's point of view in relation to the Croats was not firm - they were sometimes ranked among the South Russians, sometimes they were excluded from the environment of the East Slavic tribes.

The wide settlement of the Eastern Slavs on the East European Plain and their division into three groups did not violate their unified linguistic development. The decisive role in the unified development of the Old Russian language, as A. A. Shakhmatov believed, was played by the Kiev state. With its emergence, a “common Russian life” is formed, the process of common Russian linguistic integration develops. The leading role of Kyiv determined the unified all-Russian linguistic processes throughout the territory of Ancient Russia.

In the XIII century. the Old Russian linguistic community is disintegrating. In the following centuries, on the basis of the North Russian, East Russian and South Russian dialects of the Old Russian language and as a result of their interaction, separate East Slavic languages \u200b\u200bare formed - Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian.

The concept of A. A. Shakhmatov was a significant stimulus in the further study of the Old Russian language and nationality. It was adopted by a number of prominent linguists of that time, including D. N. Ushakov, E. F. Budde, B. M. Lyapunov. For a long time, the constructions of A. A. Shakhmatov were widespread among Russian scientists, and in some part they have not lost their significance to this day.

The Serbian linguist D.P. Dzhurovich, who made an interesting attempt to reconstruct the dialect division of the Proto-Slavic language, believed that it also included the Proto-Russian dialect, which became the basis of the Old Russian language, and localized it in the right-bank part of the Middle Dnieper, up to the basin of the upper Bug, inclusive .

Of undoubted interest are studies in the field of the origin of the East Slavic language of the Polish Slavist T. Ler-Splavinsky. He argued that the provision on the Proto-Russian (Old Russian) linguistic unity, formed during the division of the Proto-Slavic community, belongs to the indisputable. The researcher gave a detailed description of the "Proto-Russian language", describing the features that are unique to this language and alien to other Slavic languages. Until the end of the XI century. this language was divided not into three, as A. A. Shakhmatov believed, but only into two dialect groups: the northern and the more extensive southern, each of which had its own characteristic phonetic features. This division, according to T. Ler-Splavinsky, corresponded to the two cultural and political centers of Ancient Russia - Kiev and Novgorod. Kyiv united the southern tribes of the Eastern Slavs: Polyans, Drevlyans, Northerners, Radimichi, Vyatichi and, probably, others. Novgorod belonged to the lands of the Slovenian Ilmen and Krivichi.

The time of differentiation of the Old Russian language into the northern and southern branches, according to T. Ler-Splavinsky, cannot be determined from linguistic data. After the 11th century, during the period of political fragmentation of Russia, the process of gradual transformation of these dialect groups into three East Slavic languages begins. Thus, in the XIII-XIV centuries. Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian languages appear. The Russian language is formed on the basis of the consolidation of the North Russian group with a part of the South Russian. The Ukrainian language was formed entirely from the South Russian group, while the Belarusian language evolved from its northwestern part.

The constructions of T. Ler-Splavinsky were not widely used in linguistics and were accepted only by a few of its representatives.

The well-known linguist N. S. Trubetskoy tried to approach the coverage of the issues under consideration in a different way. The question of the existence of the Old Russian (Common East Slavic) language, in his opinion, should be considered firmly established. The researcher, like many of his predecessors, argued that the language development went from Proto-Slavic to Common East Slavic, and then as a result of the collapse of the latter, three independent East Slavic languages were formed. Following T. Ler-Splavinsky, N. S. Trubetskoy tried to substantiate the initial division of the common Russian language into two dialect groups, southern and northern, which differed markedly in basic phonetic features. He admitted the existence of such a division even in the pre-literate period. While the southern part of the Eastern Slavs, the scientist argued, developed in contact with the southern and western Slavs, the northern group became sharply isolated. Sound changes penetrating from the Slavic south and west did not reach the north of the eastern Slavs. Here development proceeded in contact interaction with the non-Slavic tribes of the Baltic region. This was realized later in the existence of two cultural centers in Ancient Russia: Kyiv and Novgorod. Thus, it turned out that the origin of elements of the North Russian and South Russian dialects is older than the formation of the Old Russian language.

N. S. Trubetskoy did not determine the time of formation of the common Russian language, but assumed that its two-term structure was preserved until the 60s of the XII century, when the process of the decline of the reduced ones began, dated by the researcher to 1164–1282. After 1282, the Old Russian language ceased to exist - the main phonetic changes now developed locally, not covering the East Slavic world as a whole.

N. S. Trubetskoy's research on the long-standing two-term structure of the East Slavic language caused a heated discussion. They were sharply criticized by A. M. Selishchev. N. N. Durnovo actively opposed the objections of A. M. Selishchev.

In many linguistic works of the first half of the XX century. studied (without ethnohistorical digressions) the characteristic features of the Old Russian (East Slavonic) language and its dialects, which left no doubt about the existence of a single ethno-linguistic community during the period of Kievan Rus. At the same time, research showed that the Old Russian language became the common basis for the Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian languages. In this regard, we can mention the work of N. N. Durnovo on the history of the Russian language. The researcher emphasized that the phonetic and morphological foundations of the pre-written Proto-Russian language were directly inherited from the Common Slavic.

Meanwhile, in the first decades of the 20th century, other opinions were also expressed, denying the commonality of the Eastern Slavs. Thus, the historian M.S. Grushevsky attributed the origin of the Ukrainian ethnos to the Dnieper union of the tribes of the Antes, known to Byzantine authors of the 6th century. . Some linguists tried to deny the existence of a single Old Russian language. Thus, the Austrian Slavists S. Smal-Stotsky and T. Garter, determining the relationship of languages only by the number of groups of similar features, believed that the Ukrainian language has similarities with Serbian in ten groups, and with Great Russian only in nine. Consequently, they concluded, Ukrainians once had much closer association with Serbs than with Great Russians, and there is no closer relationship between Great Russians and Ukrainians than with other Slavic ethnic groups. As a result, the researchers argued that there was no common Russian language, and the Ukrainian language goes back directly to Proto-Slavic. A similar opinion was also held by E. K. Timchenko. The constructions and conclusions of S. Smal-Stotsky met with unanimous rejection and severe criticism from linguists.

In the 20s of the XX century. V. Yu. Lastovsky and A. Shlyubsky preached the so-called "Krivichi" theory of the origin of Belarusians. They proceeded from the position that the Belarusians were direct descendants of the Krivichi, who supposedly constituted an independent Slavic people. The researchers did not provide any factual data confirming this hypothesis, but they simply do not exist.

Very interesting provisions on the issues under consideration were put forward in the 30-40s of the XX century. B. M. Lyapunov. A monolithic common Slavic language that did not know dialects, in his opinion, never existed. Already in the era of the Proto-Slavic language, there were noticeable dialect differences. However, the common Russian (East Slavonic) language was not based on a single Proto-Slavic dialect, but was formed from several ancient Proto-Slavic dialects, the speakers of which settled in the eastern part of the Slavic world.

Naming the East Slavic phonetic and morphological features that distinguished the common Russian language from the rest of the Slavic languages, B. M. Lyapunov believed that there were many dialects on the common Russian territory, and not three or two, as A. A. Shakhmatov and T. Ler-Splavinsky believed. The researcher allowed the existence in the prehistoric period of the dialects of the Polyans, Drevlyans, Buzhans and other tribal formations of the Eastern Slavs, recorded in the annals. He believed that the Rostov-Suzdal land was inhabited by a special ancient Russian tribe, whose name has not come down to us. The common Russian language, according to B. M. Lyapunov, functioned in the era of Kievan Rus, that is, in the X-XII centuries. Around the 12th century features begin to form, which later formed the specifics of the Russian and Ukrainian languages.

By the end of the 40s of the XX century. include extensive studies of the Old Russian language and its dialects by R. I. Avanesov. The concept of A. A. Shakhmatov on the differentiation of a single Russian ethnos by the 9th century. into three dialects was criticized by this linguist and was rejected as "anti-historical". R. I. Avanesov had no doubt that the Eastern Slavs once constituted a linguistic community and stood out from the common Slavic array. The formation of the Old Russian people of the era of Kievan Rus, according to the ideas of this researcher, was allegedly preceded by the East Slavic linguistic community. During the tribal period, this community included many dialects that were unstable, and their isoglosses were constantly changing. In the IX-XI centuries. in the conditions of the formation of feudalism, the settled population increases, its stability in territorial terms. As a result, a single and monolithic in origin language of the Old Russian people is formed, which, however, received unequal local coloring in different regions. This is how territorial dialects are formed, which destroyed the old tribal ones. New regional dialect formations were more stable, they gravitated towards large urban centers. At the same time, the ancient tribal isoglosses turned out to be almost completely erased, which, as R.I. Avanesov believed, makes judgments about the dialect division of the Eastern Slavs of the prehistoric period controversial. We can only talk about certain dialect features that divided the East Slavic area into northern and southern zones, as well as about narrow regional phenomena (Novgorod dialects, Pskov dialects, East Krivichi dialects of the Rostov-Suzdal land).

In the XII century. In connection with the decline of the Old Russian state, R. I. Avanesov wrote, regional trends are intensifying, which laid the foundation for the formation of linguistic features, which later became characteristic features of the three East Slavic languages. The final addition of the latter occurred several centuries later.

In the 1950s, B. A. Rybakov first attracted these archaeologists to the study of the problems under consideration. He proposed a hypothesis about the Middle Dnieper beginning of the Old Russian people. Its core, according to the ideas of the researcher, was a tribal union, formed in the 6th-7th centuries. in the Middle Dnieper (from the basins of Ros and Tyasmin on the right bank and the lower reaches of the Sula, Pel and Vorskla, as well as the Trubezh basin on the left bank, that is, parts of the future Kiev, Chernigov and Pereyaslav lands) under the leadership of one of the Slavic tribes - the Rus. The range of the latter was determined by the clothing treasures of the 6th-7th centuries. with specific metal decorations.

This territory in chronicles dating back to the 11th-12th centuries was usually called the Russian Land "in the narrow sense of this term." In the last quarter of the 1st millennium AD. e., argued B. A. Rybakov, other Slavic tribes of Eastern Europe, as well as part of the Slavicized Finnish tribes, joined the genesis of the East Slavic ethnos. However, the researcher did not consider how exactly the process of formation of the Old Russian people took place, and I believe it was impossible to do this on the basis of archeological materials.

The period of the Old Russian state with its capital in Kyiv, argued B. A. Rybakov, was the heyday of the East Slavic people. Its unity, despite the emergence of several principalities, was preserved in the era of the feudal fragmentation of Russia in the 12th-13th centuries. This unity was realized by the East Slavic population itself, which was reflected in the geographical understanding - the entire Russian land (in the broad sense) until the 14th century. was opposed to isolated estates, with princes at war with each other.

It can be noted that the attempts of historians to get involved in the study of the process of formation of the Old Russian nationality did not give the desired results. There was too little historical evidence to shed light on this complex issue. In the middle of the XX century. in historical writings, the idea prevailed that the Eastern Slavs in the 6th-7th centuries. were antes. So, for example, considered Yu. V. Gauthier. V. I. Dovzhenok wrote that the Ant language differed little from Old Russian. The latter allegedly represented the same language as Ant, but at a higher level of development. According to V.I. Dovzhenko, the basis for the consolidation of the Eastern Slavs into the Old Russian nationality was the rapid pace of socio-economic development of the population of the East European Plain, but the ethnic development during the period of Kievan Rus became the main thing along the way to the final formation of the nationality. The separation of a single ancient Russian people into separate parts, which led to the formation of three ethnic groups - Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian - should be sought in the historical setting of the XIII-XIV centuries.

A. I. Kozachenko also considered the Ants as the first nationality of the Eastern Slavs, which developed at the dawn of a class society. The flourishing of the Old Russian nationality was determined by this researcher by periods of Kievan Rus and feudal fragmentation (until the middle of the 13th century). Its consolidation was determined both by external danger and by the demand for national unity under conditions of strong princely power.

The idea of the Antes as early Eastern Slavs was not new. It goes back to the scientific works of the first half of the 19th century. So, already K. Zeiss argued that the division of the Slavic ethnic group of the VI-VII centuries. to s (k) Lven and Ants corresponds to the differentiation of the Slavic language into western and eastern branches. Ants were identified with the Eastern Slavs by many scientists, including L. Niederle, and among linguists, as noted above, A. A. Shakhmatov and some researchers of the 50-60s of the XX century.

The problem of the formation of the ancient Russian nationality was also of interest to A. N. Nasonov. According to the ideas of this historian, the initial stage of the ethnic consolidation of the Eastern Slavs is associated with the early state formation "Russian Land", which took shape at the end of the 8th - beginning of the 9th century. in the Middle Dnieper with the center in Kyiv. Its territorial and ethnographic basis was the lands of the Polyans, Drevlyans and Northerners. At the end of the IX-X centuries. The Old Russian state spread to the entire area of the East Slavic tribes, uniting two of their branches - northern and southern - into a single ethno-linguistic array.

L. V. Cherepnin linked the process of the formation of the Old Russian nationality with changes in socio-economic life, as if taking place in the 6th-9th centuries, which contributed to the rapprochement and merging of the heterogeneous Slavic population of Eastern Europe. This historian also attached significant importance to the formation of the Old Russian state, which proceeded in parallel with the formation of the nationality. However, the common language, territory, culture and economic life, as well as the struggle against external enemies, played a decisive role in this. Period X-XII centuries. L. V. Cherepnin defined it as the time of the merger of the East Slavic tribes into a “single Russian people”.

In the XII-XIII centuries, the researcher further argued, prerequisites were created for the division of the Old Russian nationality, as a result of which strengthening and political fragmentation of the territory of the Eastern Slavs caused by the Tatar-Mongol conquest, Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian nationalities are formed.

From a historical point of view, V. V. Mavrodin also tried to show the process of formation of the ancient Russian people. He argued that the basis of the Old Russian language was the Kyiv dialect - a kind of fusion of the dialects of the population of Kyiv, rather motley in ethnic and social terms. In the diversity of Kievan dialects, a linguistic unity is formed, which became the core of the language of Kievan Rus as a whole. The commonality of the political and state life of all the Eastern Slavs, according to V.V. Mavrodin, contributed to the rallying of the Slavic population of Eastern Europe into a single ancient Russian people.

Initially, this researcher believed that the process of the formation of a nationality in the era of Ancient Russia was not completed and the ensuing feudal fragmentation predetermined its division and the emergence of new ethno-linguistic formations. Later, V.V. Mavrodin began to argue that the differentiation of the Old Russian people was due not to the incompleteness of the process of its folding, not to the feudal fragmentation of Ancient Russia, but to the historical conditions that prevailed in Russia after the Batu invasion - its territorial division, the seizure of many Russian lands by neighboring states.

At present, all these constructions of historians are of purely historiographical interest.

Ethnographers also drew attention to the presence of significant elements of the commonality of the material and spiritual culture and life of the Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian peoples, dating back to a single ancient Russian people. To the common East Slavic elements characteristic of the three East Slavic peoples, ethnographers usually refer to the “three-chamber” plan of residential buildings, their lack of a foundation, the presence of an oven in the huts, fixed benches along the walls; similar types of folk clothing (women's and men's shirts, men's coats, women's hats); wedding, birth and funeral rites; similarities in the tools and processes of spinning and weaving crafts; agricultural rituals and the proximity of arable implements. An unconditional historical community is revealed by oral art (epics and songs) of the Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian peoples, as well as fine arts - embroideries and wood carvings.

The original hypothesis about the prerequisites for the formation of the Old Russian nationality was proposed by P. N. Tretyakov. According to his ideas, the East Slavic ethno-linguistic community was the result of the miscegenation of a part of the Proto-Slavs - the bearers of the Zarubintsy culture, who settled in the first centuries of our era throughout the Upper Dnieper, with the local Baltic population. The Upper Dnieper region, as the researcher believed, became the ancestral home of the Eastern Slavs. “During the subsequent resettlement of the Eastern Slavs, which culminated in the creation of an ethnographic picture known from the Tale of Bygone Years, from the Upper Dnieper in the northern, northeastern and southern directions, in particular in the rivers of the middle Dnieper, it was by no means “pure” Slavs that moved, but a population that had assimilated Eastern Baltic groups in its composition. At the same time, P. N. Tretyakov mainly considered Zarubinets antiquities, which became widespread in the 2nd century. BC e. - II century. n. e. mainly in the Middle Dnieper and Pripyat Polissya, as well as late Zarubinets and post-Zarubinets antiquities of the Dnieper region. Other, more significant processes of the Slavic development of the East European Plain, and, consequently, the complex ethnogenetic situations that took place, remained outside the researcher's field of vision.

The constructions of P. N. Tretyakov about the formation of the Old Russian people in the conditions of the Slavic-Baltic intra-regional interaction in the Upper Dnieper region do not find confirmation either in archaeological or linguistic materials. East Slavic does not show any common Baltic substratum elements. What united all Eastern Slavs linguistically in the Old Russian period and at the same time separated them from other Slavic ethnic formations of that time cannot be considered as a product of the Baltic influence.

The idea of the emergence of an East Slavic linguistic community in the area of Zarubinets culture was also expressed by the linguist F. P. Filin, however, without making any attempts to somehow support this thesis with linguistic materials. However, this is not the main thing in his important purely linguistic studies. The researcher argued that around the 7th century. n. e. The Slavs, who settled the lands east of the Carpathians and the Western Bug, are isolated from the rest of the Slavic world, which led to the emergence of a number of linguistic innovations that made up the specifics of the Old Russian language at the first stage of its development. In the works of F. P. Filin, all phonetic phenomena characteristic of the East Slavic linguistic community, and its special lexical development, received a detailed description.

The dialectal structure of the Old Russian language seemed to F. P. Filin to be complex, formed on the basis of both the dialect zones of the Proto-Slavic era inherited by the Eastern Slavs, and regional innovations that arose already in the process of the development of the East Slavic language. During the formation of the Old Russian state, the researcher argued, there were still no inclinations of the future Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian languages. There was a single Old Russian language, which had dialectal features in different areas.

In the work of 1940, F. P. Filin paid some attention to the Kiev dialect, which, in his opinion, was put forward as a common East Slavic language, that is, Old Russian. However, in subsequent studies, he no longer claimed this.

The fragmentation of Kievan Rus into many feudal principalities, according to F. P. Filin, led to an increase in dialect differences. The dialects of the Old Russian lands were now entering into a centripetal development. The turning point was the historical events of the 13th century. The Tatar-Mongol invasion and the Lithuanian conquests, which divided the East Slavic area for a long time, could not but affect the history of the language. Regional dialectisms arose in the phonetic system, phenomena developed that became specific to individual East Slavic languages. In the XIV-XV centuries, as F. P. Filin believed, one can speak of the initial stage of the formation of the Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian languages, since at that time the features characteristic of them became widespread.

The process of the formation of the Old Russian language by the Ukrainian linguist G. P. Pivtorak is somewhat vaguely described. On the one hand, referring to the works of archaeologists, he writes about two directions of the Slavic development of the East European Plain: 1) from the Middle Dnieper, moving along the Dnieper and Desna, the Slavs settled the upper Dnieper lands, the Volga-Oka interfluve and the upper reaches of the Neman; 2) from the Venetian area in the South Baltic, by sea or land, another group of Slavs settled in the forest zone, where the Krivichi and Slovenes of Novgorod are recorded in chronicles and archeology. The East Slavic ethnos, according to the researcher, was formed gradually during the settlement of Slavic tribes on the Russian Plain. The initial core of the settlement of the Old Russian people from the first half of the 1st millennium AD. e. there were lands between the upper reaches of the Western Bug and the middle Dnieper. The unity of the Old Russian language, according to G.P. Pivtorak, in the era of Kievan Rus and feudal fragmentation was constantly reinforced by various extralinguistic factors.

O. N. Trubachev sees the ancient center of the common Eastern Slavic linguistic community on the Don and the Seversky Donets. These hypothetical constructions do not seem to be sufficiently elaborated. A number of historical and philological questions arise, the answers to which modern Slavic studies cannot give.

In recent decades, the Kyiv archaeologist and historian P.P. Tolochko also addressed the problem of the ancient Russian nationality. His constructions are based on the interpretation of individual places of written monuments with some references to archeological materials and come down to the following. Already in the VI-VIII centuries. Eastern Slavs were a single ethno-cultural array, consisting of a dozen related tribal formations. Period IX-X centuries. characterized by internal migrations that contributed to the integration of the East Slavic tribes. The process received a noticeable acceleration from the end of the 9th - the first decades of the 10th century, when the Old Russian state was formed with the capital in Kyiv and the ethnonym rus approved for all Eastern Slavs.

During the IX-XII centuries. within the state territory of Kievan Rus there was a single East Slavic ethnic community. Its core, according to P.P. Tolochko, was Russia, or the Russian land “in the narrow sense”, or, in the terminology of foreign sources, “Inner Russia”, that is, the territory that in the late Middle Ages was called Little Russia.

The idea of the formation of the Old Russian language on the basis of the Proto-Russian dialect formation, traces of which cannot be identified in linguistic materials, forces researchers to look for other ways to resolve the issue of the formation of a common East Slavic ethno-linguistic unity, the existence of which in the first centuries of the 2nd millennium AD. e. is beyond doubt. Above, B. M. Lyapunov's concept of the composition of the Old Russian language on the basis of several Proto-Slavic dialect groups was outlined. Modern archaeological evidence of the Slavic development of the East European Plain also leads to this conclusion. The issue of the formation of the Old Russian people on the basis of archeological materials was thesisly considered in a number of my publications, which show that the formation of this ethno-linguistic unity was due to the leveling and integration of the Slavic tribal formations that inhabited the East European Plain, in the conditions of a single historical and cultural space formed on the territory Old Russian state. This will be discussed in more detail in the present study.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the linguist G. A. Khaburgaev also adhered to a similar point of view. He argued that a distinct Proto-Slavic dialect or Proto-Russian language never existed. East Slavic ethno-linguistic unity took shape on the basis of the spread of Slavic speech in Eastern Europe in a heterogeneous way from components that were heterogeneous in origin. On the eve of the formation of the Old Russian state, according to G. A. Khaburgaev, a process took place that actively destroyed the old tribal foundations. The political unification of various Slavic tribes led to the formation of a peculiar dialect-ethnographic East Slavic community. Archaeological monuments of the X-XII centuries. on the territory of Ancient Russia, this researcher argues, testify to a noticeable convergence of all the main cultural and ethnographic elements, to the process of consolidating the population into a single nationality.

A small discussion regarding the essence of the Old Russian people took place at the VI International Congress of Slavic Archeology, held in Novgorod in August 1996. The Belarusian archaeologist G.V. Shtykhov, using selective historical and archaeological data, argued that the Old Russian people had not yet formed in the era of Kievan Rus finally and broke up in connection with the fragmentation of the Old Russian state into many principalities. The researcher did not touch upon the linguistic materials characterizing the East Slavic community at all and concluded that “the process of the emergence of kindred East Slavic peoples - Belarusian, Ukrainian and Russian (Great Russian) - can be consistently stated without using this controversial concept” (that is, the Old Russian nationality). Apparently, G. V. Shtykhov is not embarrassed by the fact that this idea comes into conflict with the achievements of linguistics. The researcher further notes that the Slavic population of Ancient Russia spoke various dialects.

This is true, but this does not at all lead to the conclusion that there were no common phonetic, morphological and lexical phenomena in the 10th-12th centuries. affecting the entire East Slavic area.

A close position was recently taken by the Ukrainian archaeologist V. D. Baran. In a short article, mainly devoted to the culture of the Slavs of the period of the great migration of peoples according to archaeological data, he briefly concludes that the result of the Slavic migration and the interaction of the Slavs with the non-Slavic population was the formation of new ethnic formations, including the emergence of three East Slavic ethnic groups: Belarusian, Ukrainian and Russian . The Kiev state, headed by the Rurik dynasty, did not stop the ethnic process of the formation of these peoples, but only slowed it down for a while. The period of the Tatar-Mongol ruin of Russia was, according to V. D. Baran, not the beginning, but the final stage in the formation of three East Slavic peoples. No data confirming this concept can be found in archaeological materials. V. D. Baran did not even try to substantiate it in any way. It is said, however, that the ancestors of the Belarusians in the V-VII centuries. there were tribes of the Kolochin culture, but how exactly the process of the ethnogenesis of Belarusians proceeded remains absolutely unclear. After all, the East Slavic population of both the Polotsk land and the Turov volost, which formed the backbone of the emerging Belarusian nationality, was not genetically connected in any way with the carriers of the Kolochin antiquities.

Very important point in the problem under consideration is the question of the identity of the Eastern Slavs in the era of Ancient Russia as a single ethnic entity. This topic was considered earlier by D. S. Likhachev, later an interesting section was devoted to it, written by A. I. Rogov and B. N. Florey in a monographic study of the formation of the self-consciousness of the Slavic peoples in the early Middle Ages. Based on the analysis of chronicle texts, hagiographic monuments and foreign evidence, researchers argue that already in the 11th century. an idea was formed about the Russian land as a single state, covering the entire territory of the Eastern Slavs, and about the population of this state as “Russian people”, constituting a special ethnic community.

Notes

- Vostokov A. Kh. Discourse on the Slavic language // Proceedings of the Society of Lovers of Russian Literature. Issue. XVII. M., 1820. S. 5–61; Philological observations of A. Kh. Vostokov. SPb., 1865. S. 2–15.

- Sreznevsky II Thoughts on the history of the Russian language. SPb., 1850.

- Lavrovsky P.A. On the language of the northern Russian chronicles. SPb., 1852.

- Pogodin M.P. Notes on the ancient Russian language // Izv. Academy of Sciences. T. 13. St. Petersburg, 1856.

- Maksimovich M.A. Collected Works. T. P. Kyiv, 1877.

- Sobolevsky A. I. Essays from the history of the Russian language. Kyiv, 1888; His own. Lectures on the history of the Russian language. Kyiv, 1888.

- Shakhmatov A. A. To the question of the formation of Russian dialects and Russian nationalities // ZhMNP. SPb., 1899. No. IV; His own. Essay on the most ancient period in the history of the Russian language: (Encyclopedia of Slavic Philology. Issue II). Pg., 1915; His own. Introduction to the course of the history of the Russian language. Part 1. The historical process of the formation of Russian tribes and Russian nationalities. Pg., 1916; His own. The most ancient fate of the Russian tribe. Pg., 1919.

- Ushakov D.N. Adverbs of the Russian language and Russian nationalities // Russian history in essays and articles / Ed. M. V. Dovnar-Zapolsky. T. 1. M., b. G.; Buddha E.F. Lectures on the history of the Russian language. Kazan, 1914; Lyapunov B.M. Unity of the Russian language in its dialects. Odessa, 1919.

- Dzhurovich D.P. Dialects of the common Slavic language. Warsaw, 1913.

- Lehr-Splawinski T. Stosunki pokrewienstwa jezykow rukich // Rocznik slawistyczny. IX–1. Poznan, 1921, pp. 23–71; Idem. Kilka uwag o wspolnosci jezykowej praruskiej // Collection of articles in honor of Academician Alexei Ivanovich Sobolevsky (Collection of the Department of Russian Language and Literature. 101:3). M., 1928. S. 371–377; Idem. Kilka uwag o wspolnosci jezykowej praruskiej // Studii i skize wybrane z jezykoznawstwa slowianskiego. Warzawa, 1957.

- Trubetzkoy N. Einige uber die russische Lautentwicklung und die Auflosung der gemeinrussischen Spracheinheit // Zeitschrift fur slavische Philologie. bd. 1:3/4. Leipzig, 1925, pp. 287–319. The article was translated into Russian and published in the book: Trubetskoy N.S. Selected Works in Philology. M., 1987. S. 143–167.

- Selishchev A. M. Critical remarks on the reconstruction of the ancient fate of Russian dialects // Slavia. VII: 1. Praha, 1928; Durnovo N. N. Several remarks on the issue of the formation of Russian languages // Izv. in Russian language and literature. T.P.L., 1929.

- Durnovo N. N. Essay on the history of the Russian language. M., 1924. Reissue: M., 1959.

- Hrushevsky M. History of Ukraine-Rus. Ki i v, 1904, pp. 1–211.

- Smal-Stocki St., Gartner T. Grammatik der ruthenischen (ukrainischen) Sprache. Vienna, 1913; Smal-Stotsky St. Rozvytok glancing about the sim "th words" of the yang mov i ix mutually opidnennya. Prague, 1927.

- Timchenko E.K. Words "Janian unity and the camp of the Ukrainian language in the words" Jansk homeland // Ukraine. Book. 3. Kiev, 1924; His own. A course of Ukrainian language history. Kiev, 1927.

- Galanov I. Rev. on the book: Grammatik der ruthenischen (ukrainischen) Sprache. Von Stephan v. Smal-Stockyj and Teodor Garther. Wien, 1913 // Izv. Department of the Russian language and literature of the Imperial Academy of Sciences. 1914. T. XIX. Book. 3. S. 297–306; Yagich V. Rets. // Archiv fur slavische Philologie. bd. XXXVII. Berlin, 1920. S. 211.

- Lastouski V. A short history of Belarus and Vilna, 1910. More consistently, the opinion of this researcher is presented in his articles published in the journal Kryvich, which was published in 1923-1927. in Kaunas.

- Lyapunov B.M. The most ancient mutual relations of the Russian and Ukrainian languages and some conclusions about the time of their emergence as separate linguistic groups // Russian Historical Lexicology. M., 1968. S. 163–202.

- Avanesov R. I. Questions of the formation of the Russian language in its dialects // Vestnik Mosk. university 1947. No. 9. S. 109–158; His own. Questions of the history of the Russian language in the era of the formation and further development of the Russian (Great Russian) nationality // Questions of the formation of the Russian nationality and nation. M.; L., 1958. S. 155–191.

- Rybakov B. A. On the question of the formation of the ancient Russian nationality // Abstracts of reports and speeches by employees of the Institute of the History of Material Culture of the USSR Academy of Sciences, prepared for a meeting on the methodology of ethnogenetic research. M., 1951. S. 15–22; His own. The problem of the formation of ancient Russian nationality // Vopr. stories. 1952. No. 9. S. 42–51; His own. Ancient Rus // Sov. archeology. T. XVII. M., 1953. S. 23–104.

- Gotye Yu. V. The Iron Age in Eastern Europe. M., 1930. S. 42.

- Dovzhenok V.I. On the question of the composition of the ancient Russian nationality // Reports VI scientific conference Institute of Archeology. Kyiv, 1953, pp. 40–59.

- Kozachenko A.I. Old Russian people- the common ethnic base of the Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian peoples // Sov. ethnography. T. P. M., 1954. S. 3–20.

- Zeuss K. Die Deutschen und die Nachbarstamme. Munchen, 1837, pp. 602–604.

- Niederle L. Slavic antiquities. M., 1956. S. 139–140.

- Yakubinsky A.P. History of the Old Russian language. M., 1941. (Reprint: M., 1953); Chernykh P. Ya. Historical grammar of the Russian language. M., 1954; Georgiev Vl. Veneti, anti, sklaveni and tridelenieto in Slavonic Yezitsi // Slavonic collection. Sofia, 1968, pp. 5–12.

- Nasonov A.N. To the question of the formation of the ancient Russian nationality // Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. 1951. No. 1. S. 69–70; His own. "Russian land" and the formation of the territory of the ancient Russian state. Moscow, 1951, pp. 41–42.

- Cherepnin L. V. Historical conditions for the formation of the Russian nationality until the end of the 15th century. // Issues of the formation of the Russian people and nation. M., 1958. S. 7–105.

- Mavrodin VV Formation of the Old Russian state. L., 1945, pp. 380–402; His own. Formation of a unified Russian state. L., 1951. S. 209–219; His own. The formation of the Old Russian state and the formation of the Old Russian nationality. M., 1971. S. 157–190; His own. Origin of the Russian people. L., 1978. S. 119–147.

- Tokarev S.A. On the cultural community of the East Slavic peoples // Sov. ethnography. 1954. No. 2. S. 21–31; His own. Ethnography of the peoples of the USSR. M., 1958; Maslova G.S. Historical and cultural ties between Russians and Ukrainians according to folk clothes // Ibid. pp. 42–59; Sukhobrus G. S. The main features of the commonality of Russian and Ukrainian folk poetic creativity // Ibid. pp. 60–68.

- Tretyakov P.N. Eastern Slavs and the Baltic Substratum // Sov. ethnography. 1967. No. 4. P. 110–118; His own. At the origins of the ancient Russian people. L., 1970.

- Sedov V.V. Once again about the origin of the Belarusian nationality // Sov. ethnography. 1968. No. 5. S. 105–120.

- Filin F.P. On the origin of the Proto-Slavic language and East Slavic languages // Vopr. linguistics. 1980. No. 4. S. 36–50.

- Filin F. P. Essay on the history of the Russian language until the XIV century. A. I. Herzen. T. XXVII. L., 1940; His own. The formation of the language of the Eastern Slavs. M.; L., 1962; His own. The origin of the Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian peoples: a historical and dialectological essay. L., 1972.

- Filin F.P. Essay on the history of the Russian language ... S. 89.

- Pivtorak G.P. Formation and dialect differentiation of old Russian language: (Historical and phonetic drawings). Kiev, 1988.

- Trubachev O. N. In search of unity. M., 1992. S. 96–98.

- Tolochko P.P. Ancient Russia: Essays on socio-political history. Kyiv, 1987, pp. 180–191; His own. Chi isnuvala old-Russian populism? // Archeology. Kiev, 1991. No. 3. S. 47–57.

- Sedov V.V. Eastern Slavs in the 6th–13th centuries. M., 1982. S. 269–273; His own. Slavs in the Early Middle Ages. M., 1995. S. 358–384.

- Khaburgaev G. A. Formation of the Russian language. M., 1980.

- Shtykhov G.V. Old Russian nationality: realities and myth // Ethnogenesis and ethnocultural contacts of the Slavs: Proceedings of the VI International Congress of Slavic Archeology. T. 3. M., 1997. S. 376–385. In the discussion on the report of G. V. Shtykhov, he was supported by I. A. Marzalyuk, A. I. Filyushkin, and O. N. Trusov (Ibid., pp. 386–388). Unfortunately, linguists did not take part in the dispute.

- Baran V.D. The great spread of words "yan" // Archeology. Kiev, 1998. No. 2. S. 30–37. In the book "Ancient Slavs" this researcher expressed a different idea. He believes that the carriers were the basis of all East Slavic chronicle tribes The collapse of the Kievan state after the death of Yaroslav the Wise led to the grouping of the Slavic population of Eastern Europe around three main cultural and economic centers: Polotsk on the Western Dvina, Vladimir on the Klyazma and Kyiv with Galich in the Dnieper-Dniester These regions preserved the traditions of the era of the great migration of peoples and became the foundations of the three East Slavic peoples - Belarusian, Russian and Ukrainian (Baran V. D. Davni slov "jani. Kiev, 1998. S. 211-218).

- Likhachev D.S. National identity of Ancient Russia. M.; L., 1945.

- The development of the ethnic identity of the Slavic peoples in the early Middle Ages. M., 1982. S. 96–120.

Slavic cultural and tribal formations in the southern regions of the East European Plain on the eve of the formation of the Old Russian people

In the first centuries of our era, the Slavs inhabited parts of the territories of two archaeological cultures: Przeworsk, occupying Central European lands from the Elbe to the Western Bug and the upper Dniester, and Chernyakhov, which spread in the Northern Black Sea region from the lower Danube in the west to the Seversky Donets in the east. These cultures were large polyethnic formations of a provincial-Roman appearance. The Slavs, called Wends by ancient authors, in the area of the Przeworsk culture belonged to the lands of the Middle and Upper Hanging with adjacent areas of the Oder basin and the Upper Dniester. This region was not closed, it was repeatedly invaded by various Germanic tribes. On the territory of the Chernyakhov culture, in the conditions of marginal mixing of the local Late Scythian-Sarmatian population and the settled Slavs, a Slavic-Iranian symbiosis developed, as a result, a separate dialect-tribal formation of the Slavs, known in historical sources as antes, became isolated in Podolia and the Middle Dnieper region.

The invasion of the Huns significantly disrupted the historical situation that had developed in Roman times in Eastern and Central Europe. The Huns, originating from Central Asia, in the II century. n. e., as evidenced by Dionysius and Ptolemy, appeared in the Caspian steppes, where they lived until the 70s of the 4th century. Having defeated the Alano-Sarmatians, who roamed the steppes between the Volga and the Don, in 375 the Huns invaded the northern Black Sea lands in powerful hordes, crushing everything in their path, robbing dwellings and burning villages of the Chernyakhov culture, devastating fields and killing people. Archeology shows that a significant number of Chernyakhiv settlements at the end of the 4th c. ceased to exist, the craft centers that functioned here, supplying the surrounding population with various products, were completely destroyed. Eunapius, a contemporary of the Hun invasion, wrote: “The defeated Scythians (as the ancient authors called the population of the former Scythia) were exterminated by the Huns and most of them died ...” By the end of the 4th century. the entire Chernyakhov culture ceased to function, only in certain areas of the forest-steppe zone relatively small islands of its settlements were preserved. Separate groups of the Chernyakhov population fled, as evidenced by archeological data, to the north to the southern regions of the Oka basin and to the Crimea. At the same time, other hordes of the Huns headed for Taman and the Crimea - the rich cities of the Bosporus were subjected to devastating pogroms, and their inhabitants were massacred.

Having defeated the Visigoths somewhere on the lower Dniester, the Huns invaded the Danube lands and at the beginning of the 5th century. mastered the steppe expanses of the Middle Danube, where, having subjugated the surrounding tribes, they soon created a powerful Hun state. Having settled in Central Europe, the Huns also kept the northern Black Sea tribes in their power.

The invasion of the Huns significantly affected the Przeworsk culture. The main part of its craft centers and workshops, which supplied the agricultural population with their products, ceased to function, and many villages were deserted. At the same time, there was an outflow of significant masses of the population from the area of the Przeworsk culture. Thus, the Germanic tribes, recorded by Roman authors in the Vistula-Oder region, went south to the borders of the Roman Empire. The Slavs also joined the whirlpool of the great migration of peoples. In the first decades of the 5th c. Przeworsk culture ceased to function.

The situation was aggravated by a significant deterioration in the climate. The first centuries of our era were climatically very favorable for the life and management of the agricultural population, which formed the basis of the bearers of the Przeworsk culture. Archeology clearly records in the III-IV centuries. and a significant increase in the number of settlements, and a noticeable increase in population, and the active development of agricultural technology.

From the end of the 4th century in Europe, a sharp cooling sets in, the 5th century was especially cold. It was a period of maximum cooling not only for the 1st millennium AD. e., at this time the lowest temperatures in the last 2000 years were observed. Soil moisture increases sharply, which was due to both an increase in precipitation and the transgression of the Baltic Sea. The levels of rivers and lakes are noticeably rising, groundwater is rising, swamps are growing. As a result, many settlements of the Roman period were flooded or severely flooded, and arable land was unsuitable for agricultural activities. Archaeological surveys in northern Germany have shown that the level of rivers and lakes here has risen so much that the population was forced to leave most of the villages that functioned in Roman times. As a result, the Teutons abandoned the lands of Jutland and adjacent regions of mainland Germany. From floods and waterlogging, the Middle Vistula, which is distinguished by low relief, was seriously affected. Here, almost all the settlements of the Roman period by the beginning of the 5th century BC. abandoned by the agricultural population. As shown below, significant masses of the inhabitants of this region migrated to the northeast, moving along the elevated lacustrine-glacial ridges from the Masurian Lakes to Valdai.

The Hun conquests in Europe were interrupted in 451, when the Hun troops invading Gaul were defeated in the battle on the Catalan fields. A year later, the well-known Hun leader Attila (445-454), having gathered a powerful army, again moved to Gaul, but could not conquer it, and after his death the Hun state collapsed. The life of the agricultural population preserved in more or less large islands in the areas of the Przeworsk and Chernyakhov cultures, and these were mostly Slavs, gradually stabilized. Deprived of the products of the provincial Roman crafts, the population was forced to create life and culture anew. At first, the early medieval Slavs in terms of development turned out to be lower than in the Roman period.

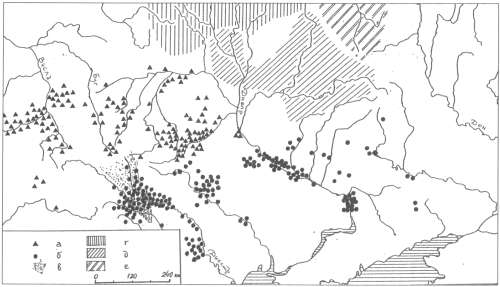

The Slavs entered the Middle Ages as a far from monolithic mass. Geographically, they were scattered over a wide area of Central and Eastern Europe. Communications between individual regions were often absent. The historical situation in each of them was peculiar; in a number of places, more or less large groups of Slavs settled among other ethnic aborigines. As a result, in the V-VII centuries. there were several different Slavic cultures recorded by modern archeology (Fig. 1).

rice. 1. The resettlement of the Slavs during the Great Migration of Peoples

(a) area of the Sukovsko-Dziedzitsa culture;

b - Prague-Korchak culture;

c – Penkovskaya culture;

d – hyposhty-Kyndeshti antiquities;

e - Imenko culture;

(f) cultures of the Pskov long mounds;

g - Tushemla culture;

h - "Meryanskaya" culture;

and – antiquities of the Udomel type;

j - regions of residence of the Slavs in Roman times;

l - the main directions of the beginning process of development by the Slavs of the Balkan Peninsula

Notes

- For more on this, see: Sedov V.V. Origin and early history of the Slavs. M., 1979. S. 119-133; His own. Slavs in antiquity. M., 1994. S. 233-286.

- Latyshev VV News of ancient writers about Scythia and the Caucasus. T. I. Greek writers. SPb., 1893. S. 726.

Anty

During the 5th century in the Podolsk-Dnieper region of the territory of the former Chernyakhov culture, the Penkovo culture is being formed (Fig. 2). Its creators were the descendants of the population of the forest-steppe strip of the Chernyakhovsky area, that part of it, where in Roman times, under the conditions of the Slavic-Iranian symbiosis, Antes were formed. In addition, during the formation of Penkovo antiquities, there was an influx of migrants from the Dnieper left-bank lands, as evidenced by the elements of Kievan culture, manifested in house building and in ceramic materials.

rice. 2. Areas of the Prague-Korchakov and Penkov cultures

a - monuments of the Prague-Korchak culture (Duleb group);

b – monuments of the Penkovo culture (Antskaya group);

c - the direction of migration of the carriers of the Prague-Korchak antiquities to the lower Danube;

(d) area of the Tushemla culture;

(e) area of the Kolochin culture;

(f) area of the Moshchin culture;

Monuments of the initial stage of the Penkovo culture were studied in the Middle Dnieper and on the Southern Bug. Such, in particular, are the settlements of Kunya, Goliki and Parkhomovka, excavated by P. I. Khavlyuk in the Bug region, on which semi-dugout dwellings heated by heaters or hearths were discovered, and characteristic stucco pottery was found. At the settlement of Kunya, an iron two-membered fibula with a long shackle and a solid flat receiver was found, dating from the end of the 4th–5th centuries; In the semi-dugout dwellings at the settlement of Kochubeevka, along with Penkovo utensils, fragments of Chernyakhov pottery were also found. Such utensils were also found in some other Penkovo settlements, apparently survivingly used at the beginning of the Middle Ages.

In the Middle Dnieper region, one of the studied sites with cultural layers of the 5th century. is the settlement of Hittsi. The bulk of the pottery here was typically Pennovsky hand-made utensils. Some vessels combined the features of Penkovo and Kiev ceramics in form. Fragments of Chernyakhov pottery were also found. The dating find here is a bone comb from the 5th century BC.

To the early stage of the Penkovo culture belongs one of the ground burial grounds near the village. Velikaya Andrusovka on the river. Tyasmin. His excavations revealed burials according to the rite of cremation on the side. The remains of the cremation were poured into small pits. In one of these burials, a cast bronze buckle dating back to the 5th century was found.

In the next century, the population of the Penkovo culture is actively growing and developing new territories. The culture is characterized by a number of features, among which the most striking is ceramics (Fig. 3: 4–6). Its leading form was pots with a slightly profiled upper edge and an oval-rounded body. The greatest expansion of these pots falls on the middle part, the neck and bottom are narrowed and approximately equal in diameter. The second common type of vessels are biconical pots with a sharp or slightly smoothed edge. In addition, flat clay discs and frying pans, characteristic of most Slavic cultures of the early Middle Ages, and occasionally bowls are common at Penkovo sites. All these dishes were made without a potter's wheel. Ornamentation on the vessels, as a rule, is absent, only a few pots have notches along the edge of the rim, a molded roller or moldings in the form of knobs on the body.

![]()

rice. 3. Ceramics of the Prague-Korchak (1-3) and Penkovo (4-6) cultures

1-3 – from the Korchak IX settlement and the Korchak burial ground;

4-6 - from the village of Semenki

The main type of settlements were unfortified settlements with an area of no more than 2-3 hectares. In most villages, there were from 7 to 15 households at the same time. Unsystematic building dominated, only a few settlements had a row type of building. The dwellings were sub-square semi-dugouts with an area of 12 to 20 square meters. m. The depth of the pits ranges from 0.4 to 1 m. The walls of the buildings had a log or pillar construction, log dwellings predominated. Log cabins were cut "in the cloud" or "in the paw". Their ground parts rose by 1.5-2m. With a pillar structure, the blocks were laid horizontally along the walls of the pit and fastened with stakes or by letting their ends into the grooves of the risers. The roofs of the dwellings had wooden frames, which were covered with straw, reeds or poles smeared with a layer of clay.

Dwellings were heated by stoves or hearths. At the early stage of the Penkovo culture, hearths predominated, later stove-heaters dominated, usually occupying one of the corners of buildings. In rare cases, clay ovens have also been recorded. The floors of the dwellings were rammed, mainland; only in a few buildings the floor was lined with wooden planks. In many buildings opposite the stoves, recesses were cut out for descending a wooden staircase, sometimes steps were cut into the mainland soil. The interior of the Penkovsky dwelling is unpretentious - only wall benches were arranged.

Dwellings in the Penkovsky settlements were accompanied by outbuildings. These were either above-ground log or column structures, or, more often, cylindrical, bell-shaped or barrel-shaped pits-cellars from 0.3 to 2 m in diameter and up to 2 m deep. They stored grain and other food supplies.

In the southern regions of the Dnieper region, where the population of the Penkovo culture was in close contact with the nomadic world, in a number of settlements, recessed dwellings of a round or oval shape were discovered, reminiscent of nomad yurts and indicating the infiltration of the Alan-Bulgarian population into the environment of the Slavs.

In the area of the Penkovo culture, there are also isolated fortified villages. Among them is the well-studied ancient settlement of Selishte in Moldavia, 130 x 60 m in size, arranged at the confluence of the Vatich stream into the river. Reut. From the floor side, it was reinforced with a wooden wall and a deep canyon. Excavations revealed 16 semi-dugout dwellings and 81 utility pits. In four semi-dugouts, the remains of handicraft activities related to jewelry and pottery were recorded. Researchers of the monument believe that the ancient settlement was one of the administrative and economic centers of the Penkovsky area.

One of the most interesting monuments of the Penkovo culture is the Pastirskoye settlement with stratifications of the 6th-7th centuries, located in the Tyasmina basin. It occupied an area of about 3.5 hectares and was protected by ramparts and ditches built back in the Scythian time. Excavations have explored about two dozen dwellings, semi-dugouts with stoves, heaters, typically of Penkovo appearance. In addition, workshops for iron processing, a forge and pottery kilns for firing pottery are open. Collected abundant and varied clothing material. Stucco pottery of the Penkovo types was predominant in the settlement. At the same time, vessels of a nomadic appearance and pottery of the so-called pastoral type, convex-sided gray-glazed pots, were found here. In all likelihood, this ceramics goes back to the Chernyakhov pottery.

The pastoral settlement was a large trade and craft and, most likely, an administrative center, in which a diverse population lived. In addition to Slavic dwellings, the remains of yurt-like buildings of nomads were discovered here.

On the territory of the Penkovo culture, the Gaivoron iron-making complex, located on the island of the Southern Bug, was studied. On an area of 3000 sq. m, excavations revealed 25 industrial furnaces, of which 4 were sintering furnaces (for enrichment of iron ore), in the rest iron smelting was carried out.

Funeral monuments of the Penkovo culture are exclusively ground burial grounds. Its bearers and direct descendants of the Ants did not know the kurgan rite at all. The Penkovsky area was characterized by biritualism, most likely inherited from the Chernyakhov culture.

The most studied cemeteries of the Penkovo culture are the above-mentioned monument near the village. Velikaya Andrusovka and the Selishte necropolis in Moldavia. Burials according to the rite of cremation of the dead on the side, followed by the placement of calcined bones in shallow pits with a diameter of 0.4–0.6 m and a depth of 0.3–0.5 m, were recorded everywhere, burials according to the rite of inhumation are more rare.

The fertile lands occupied by the bearers of the Penkovo culture, finds of agricultural tools (iron spears, sickles, hoes), grain pits, typical for all settlements, and osteological materials definitely indicate that agriculture and animal husbandry were the basis of the economy. Among the crafts, ironworking and bronze casting were the most actively developed. Technological analyzes of iron products reveal the inheritance of the production achievements of the Roman period by the Penkovsky population.

A series of treasures and random finds of various jewelry. Among the treasures stands out Martynovsky, found in 1909 in the basin of the river. Rosi and containing up to a hundred silver items - forehead rims, earrings, temporal rings, a neck torc, bracelets, a fibula, belt accessories (plaques, tips and onlays), as well as two silver bowls with Byzantine hallmarks, a fragment of a dish, a spoon and nine stylized figures people and animals.

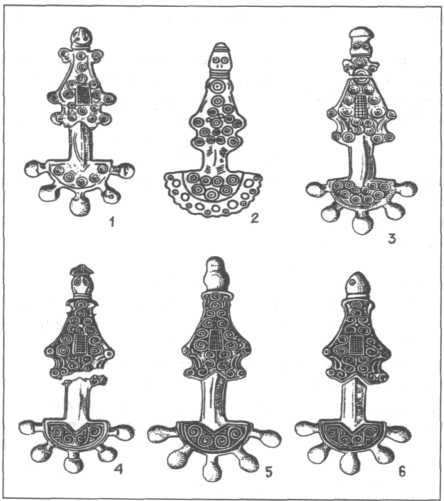

A very interesting and widespread category of finds are finger fibulae, which had semicircular shields with five to seven protrusions (Fig. 4). They were found as part of hoards, at several Penkovo settlements and in burials. At the settlement of Barnashevka in the Vinnitsa region. the production complex of the third quarter of the 1st millennium AD was opened. e., in which a casting mold for the manufacture of finger fibulae was found.

rice. 4. Finger brooches with a mask-like head from the Antian sites of the Northern Black Sea region

A large amount of literature is devoted to finger fibulae with mask-like heads and their derivatives, usually called brooches of the Ant type. In particular, I performed a generalization with distribution maps. Such brooches were an integral part of the women's clothing of the Slavic ethno-tribal group, represented by the Penkovo culture. In addition, these adornments are known in those regions of the early medieval Slavic world (the Danube, the Balkan Peninsula and part of the South-Eastern Baltic), in the settlement of which, as evidenced by other archeological data, people from the northern Black Sea lands participated.

The ethnonym of the Slavic group represented by the culture in question is defined. These are the Antes, known from the historical writings of the 6th-7th centuries. Jordanes, who completed his work "Getica" in 551, reports that the Antes were part of the Venedian Slavs and lived in the territory "from Danastra to Danapra". The researchers of this monument claim that Jordanes borrowed this information from Cassiodorus, who wrote at the end of the 5th - beginning of the 6th century. Therefore, the indicated geographical coordinates should refer to the initial phase of the Penkovo culture and correspond to the Podolsk-Dnieper region of the Chernyakhov culture.

Procopius of Caesarea, a Byzantine historian of the middle of the 6th century, reports on a wider settlement of the Antes. Their western limit at that time was the northern bank of the Danube (Istra), and in the east the Ant settlements extended to the land of the Utigurs, who lived in the steppes of the Sea of Azov, which corresponds to the general territory of the Penkov culture.

Thus, according to archaeological data, the Antes, according to archaeological data, are a large tribal group of Slavs that formed in the interfluve of the Dniester and Dnieper in late Roman times with the participation of the local Iranian-speaking population and settled at the beginning of the Middle Ages in the area from the lower Danube to the Seversky Donets. According to paleoanthropological data, a significant part of the population of the 10th–12th centuries. Southern Russia, characterized by mesocrania with relative narrowness, goes back to that group of bearers of the Chernyakhov culture, which developed under the conditions of assimilation of the Scythian-Sarmatian tribes.

Procopius of Caesarea reports that the Antes, like the rest of the Slavs, used the same language, they had the same way of life, common customs and beliefs, and earlier they were called by the same name - Wends. At the same time, it is obvious from historical sources that the Antes somehow stood out among other Slavs, since they are called on a par with such ethnic groups of that time as the Huns, Utigurs, Medes, etc. The Byzantines somehow distinguished the Anta from the Slav, even among mercenaries of the Empire.

The peculiarity of the Penkovo culture speaks of some ethnographic specificity of the Ants. There is reason to believe that the Antes constituted a special dialect group of the Late Proto-Slavic language. Full characteristic Antian dialect is difficult, but it is possible to think that it stood out among other Proto-Slavic dialect formations, primarily by the presence of a large number of Iranianisms.

According to V. I. Abaev, the change of the explosive g characteristic of the Proto-Slavic language into the posterior palatal fricative g (h), which is recorded in a number of Slavic languages, is due to the Scythian-Sarmatian influence. Since phonetics, as a rule, is not borrowed from neighbors, the researcher argued that the Scytho-Sarmatian substratum should have participated in the formation of the southeastern Slavs (in particular, future Ukrainian and South Russian dialects). Comparison of the range of the fricative g in the Slavic languages with the regions inhabited by the Antes and their direct descendants definitely speaks in favor of this position. V. I. Abaev also admitted that the result of the Scythian-Sarmatian influence was the appearance of the genitive-accusative in the East Slavic language and the proximity of East Slavic with the Ossetian language in the perfective function of preverbs. V. N. Toporov explains the origin of the unprepositional locative-dative by the influence of the Iranians. These phonetic and grammatical features in the Slavic world are regional. Their geographical distribution allows the idea of their origin in the Ant dialect of the Proto-Slavic language.

The penetration into the Slavic pagan pantheon of the gods Khors and Simargl, recorded in Russian chronicles, is also connected with the Iranian world of the Northern Black Sea region. V. I. Abaev wrote about etymological and semantic parallels between the Ukrainian Viy and the Iranian god of the wind, war, revenge and death (Scythian Vauhka-sura), between the East Slavic Rod and the Ossetian Naf.

In the Slavic ethnonymicon, indisputable Iranianisms are also known. These are, in particular, the tribal names of Croats and Serbs. The appearance of these tribal groups in the Danube basin and on the Elbe, as archeological evidence shows, was the result of the great Slavic migration of the early Middle Ages. Their ancestors in Roman times lived somewhere in the Chernyakhovsky area of the Northern Black Sea region. The ethnonym itself antes also has a Scythian-Sarmatian origin. “Of all the existing hypotheses, it seems to be more probable,” F. P. Filin wrote in this regard, “is the hypothesis about the Iranian origin of the word antes: ancient. Indian antas "end, edge", anteas "located on the edge", Ossetian. att "iya "rear, behind". This point of view is shared by many scientists, including O. N. Trubachev. That is, the Antes are outlying inhabitants. And indeed they inhabited the southeastern outlying territory of the Slavic world both in Roman times and in at the beginning of the medieval period Full semantic correspondence is observed with the name of the region of Ukraine, from where the modern ethnonym Ukrainians. The group of Slavs under consideration, apparently, was called Ants by the Scythian-Sarmatians of the Northern Black Sea region.

There is very little historical evidence to study the socio-political structure of the Ants. At the end of the IV century. in the conditions of enmity between the Goths and the Antes, the existence of a tribal formation of the latter seems undoubted. Jordan reports that initially the Antes repulsed the attack of the Gothic army, but after a while the Gothic king Vinitary still managed to defeat the Antes and executed their prince Bozh (Boz) with seventy elders. This event, judging by indirect data, took place somewhere in the region of the Erak River, usually identified with the Dnieper.

At the beginning of the Middle Ages, the Antes, as can be assumed on the basis of historical data, did not create a common political association - a single tribal union headed by archon princes. Archaeological materials say nothing about this either. From the text of Jordanes' work, one can guess that in the 6th century, apparently, there were several Antian tribal formations, each of which had its own prince. Procopius of Caesarea reports that the Antes "... are not controlled by one person, but since ancient times they have lived in democracy, and therefore they have profitable and unprofitable business always carried out together." In other words, the Antes, according to Procopius, did not know the sovereign power, similar to the Byzantine one, and lived on the basis of self-government, discussing all common issues at tribal gatherings.